Experiments with amplitude modulation in the 10m band

The oldest modulation method for transmitting audio signals (e.g., speech or music) is amplitude modulation (AM). Its efficiency depends heavily on the concepts used at both the transmitter and receiver, offering technically minded amateurs a wide field for experimentation. For example, old AM CB radios can be modified for the 10-meter band with minimal effort. Unlike CB radio, licensed amateur radio operators are permitted to convert such devices in a way to achieve greater ranges. Even building a complete 10-meter amateur radio with amplitude modulation is not very difficult. A design divided into individual functional units allows for subsequent modifications. This enables the comparison of different modules and the identification of optimal solutions. Due to the favorable characteristics of the 10-meter amateur band, radio contacts around the globe can be established under good propagation conditions, even with low transmitter power and small antennas. Under less favorable propagation conditions, the 10-meter band is well-suited for local communication. Relatively small antenna dimensions are sufficient, making the equipment ideal for mobile or portable use. Especially with amplitude modulation, additional equipment or the use of special techniques, such as HAPUG modulation, can often significantly increase the range with low transmitter power. Therefore, experiments with simple 10-meter amateur radio devices can be very rewarding.

Further articles on AM modulation and 10m amateur radio technology

- Minimalist add-on device, to use a medium wave radio as a two-way radio.

- 10m converter with diode ring mixer for conversion to the 2m band

- Homemade handheld radios with superregenerative receiver and squelch

- Crystal controlled 10m receivers using integrated circuits

- Modification of CB radio oldtimers for FM operation in the 10m band

- Using a CB mobile antenna for stationary 10m operation

- antenna splitter for simultaneous 10m radio operation and broadcast reception

- A homemade SWR and PWR meter and instructions for the use

Modification of old AM-CB radios for the 10m band

Older CB radios for AM often use separate crystals for the transmitter and receiver. This means that one transmitter crystal and one receiver crystal are required for each channel. To use all channels, a 12-channel radio operating on this principle therefore needs a total of 24 crystals, which can be selected using a 12-position switch. Such radios can be converted for the 10-meter band by replacing the crystals. This also requires changes in the resonant circuits for the higher frequencies of the 10-meter band. Usually, a simple retuning by light screw out of the coil cores is sufficient. If this isn't enough, the coil cores can be shortened by breaking them off, or the resonant circuit capacitors may need to be replaced with smaller ones – for example, 27 pF instead of 33 pF.

One problem, however, is that such crystals are difficult to obtain. CB radios of this type use crystals for the transmitter that oscillate directly at the frequency specified for the respective channel. Because the receivers of such devices typically operate on the single superheterodyne principle with an intermediate frequency of 455 kHz, the receiver crystals must oscillate at a frequency that is at this value higher or lower by this amount, e.g., 28.545 MHz or 29.455 MHz for a receiving frequency of 29 MHz. These are overtone crystals with a fundamental frequency of about one-third of the printed frequency, around 9 MHz, wich are no longer stocked by radio retailers, meaning they would have to be custom-made. This is quite expensive and likely beyond the scope of most DIY projects.

Replacing the individual crystals for the 10m amateur band

The circuit shown here was originally designed to convert old AM CB radios with individual crystals for repeater operation in the 10-meter band. Later, complete 10-meter FM homebrew radios were also built on this basis. The frequency generation is a so-called super-VFO. Here, the signal from a variable-frequency oscillator (e.g., 2.85–3.05 MHz) is mixed with that of a frequency-stable crystal oscillator. Due to the low tuning frequency, the crystal stability is almost entirely transferred to the filtered mixture. In this way, frequencies between 29.5 and 29.7 MHz can be tuned.

The mixer is an asymmetrically balanced design in which the crystal signal at the output is significantly reduced even without any selection circuitry. This design was already used in the legendary Collins transmitters and transceivers – there, equipped with triodes. With a VFO frequency range of 2.55 to 2.65 MHz, an operating frequency range of 29.0 to 29.1 MHz is also possible. In this range, some amateur radio operators still experiment today with amplitude modulation, a technique that unfortunately has otherwise largely fallen into oblivion.

The 455 kHz higher mixing product for the receiver (e.g., 29.955–30.155 MHz for FM) is obtained by crystal switching. For FM, it is desirable to be able to use a device modified in this way for repeater operation as well. This can also be achieved by crystal switching. All the necessary crystals are present in such CB radios in their original state, so no special crystals need to be obtained.

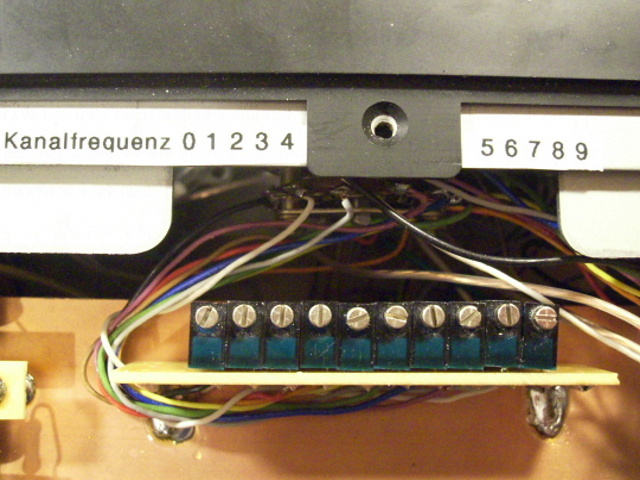

For tuning, a potentiometer with fine adjustment is recommended. If sufficient VFO frequency stability is ensured through appropriate construction and a sufficiently stabilized supply voltage, the original channel switch can also be used to set the frequency by switching between the wipers of several spindle trimmers preset to the desired frequencies. To use the circuit to control an old CB radio, the RX output is connected to the base of the transistor in the receiver oscillator. All crystals from the transmitter and receiver are removed from their sockets or desoldered. The TX output of the circuit is connected to the base of the transistor in the transmitter oscillator.

Two-stage transistor transmitter for 28...29,7 MHz

This crystal-controlled miniature transmitter for the 10-meter band is suitable for small, home-built radios. In principle, it could also be used in CB radios or as a telemetry/remote control transmitter, although this is not permitted without further ado. In amateur radio, it could also be used as a telegraphy or beacon transmitter. Suitable crystals are those whose third harmonic is at the desired transmission frequency. The oscillator uses a PNP transistor. This minimizes the effort required for matching to the directly connected power amplifier stage, which uses an NPN transistor. The transmitter output incorporates a two-stage Pi low-pass filter, which significantly reduces harmonic radiation.

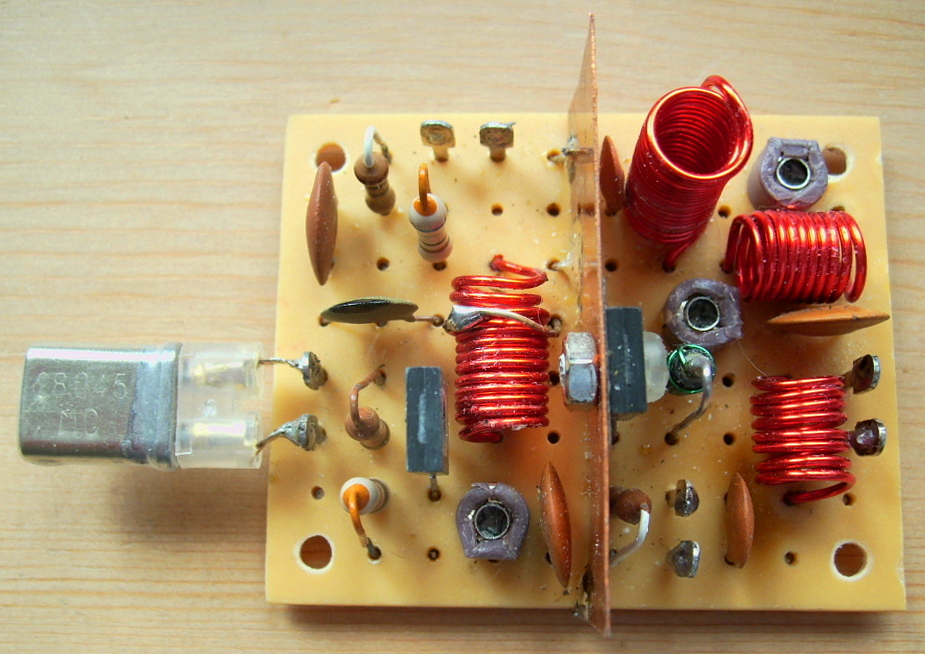

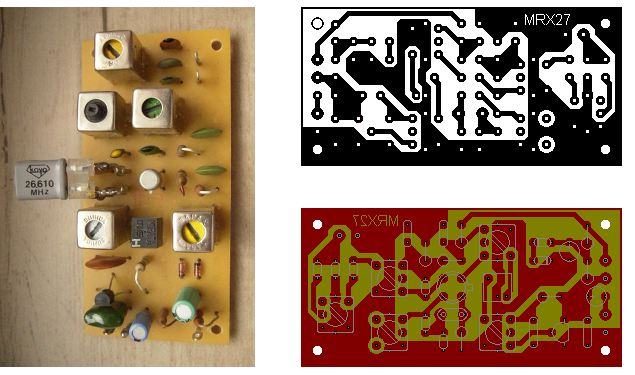

The achievable RF output power (carrier value) of this small transmitter is on the order of about half a watt. Modulation is achieved by coupling the audio signal to the emitter of the power amplifier transistor. This method, often referred to as emitter modulation, causes current flow angle control in the RF output stage wich is operating in class C. This allows for a quite usable and good intelligible amplitude modulation with minimal effort. A circuit originally designed for driving a small loudspeaker serves as the modulation amplifier. The required audio power for this type of modulation is significantly lower than the RF power of the transmitter. If the amplifier's power is too high, a resistor should be inserted into the modulation line to prevent overmodulation. The output of the modulation amplifier is otherwise connected directly to the transmitter's modulation input after the output capacitor. With a suitable switching arrangement, such as a multi-pole switch or a relay, the modulation amplifier in a radio can be used to drive the loudspeaker during receive operation. The measuring instrument allows for easy monitoring of emitter current and modulation. In a radio, the same instrument can be used as an S-meter during receive operation. As the illustration shows, such a transmitter can be easily built in a small space without special components. The circuit board dimensions are only 55 x 45 mm. A shield between the oscillator and output stage also serves as a heat sink for the RF output stage. It is made of copper sheet. The transistor is mounted on it with a plastic screw and insulated with a mica plate.

The coils are air-core coils with an 8 mm diameter. They were made by winding them around the shank of a suitable twist drill. The oscillator coil has 12 turns, the PA coil 16 turns, the PA-side coil of the output filter 10 turns, and the antenna-side coil 8 turns. The oscillator coil is tapped 3 turns from the ground end. To prevent mutual interference, the coils are positioned at 90° angles to each other.

Three-stage AM transistor transmitter for 28...29.7 MHz

The three-stage transmitter shown here is essentially a replica of the circuit from an old CB radio. It proved to be particularly easy to replicate. The necessary coils could be taken from a device with a similar circuit. Using the component values specified, the transmitter can achieve a power output of approximately 1 watt.

When connecting the modulation transformer, it is important that the DC currents from the transmitter power amplifier and the modulator output stage flow through the transformer in reverse. The windings of the push-pull output transformer used, which came from a transistor audio output stage, therefore had to be connected in opposite directions. With different component values, a carrier power of approximately 4 watts can easily be achieved with the transmitter's RF circuitry. However, to obtain sufficiently strong modulation, in this case a push-pull modulator should be used.

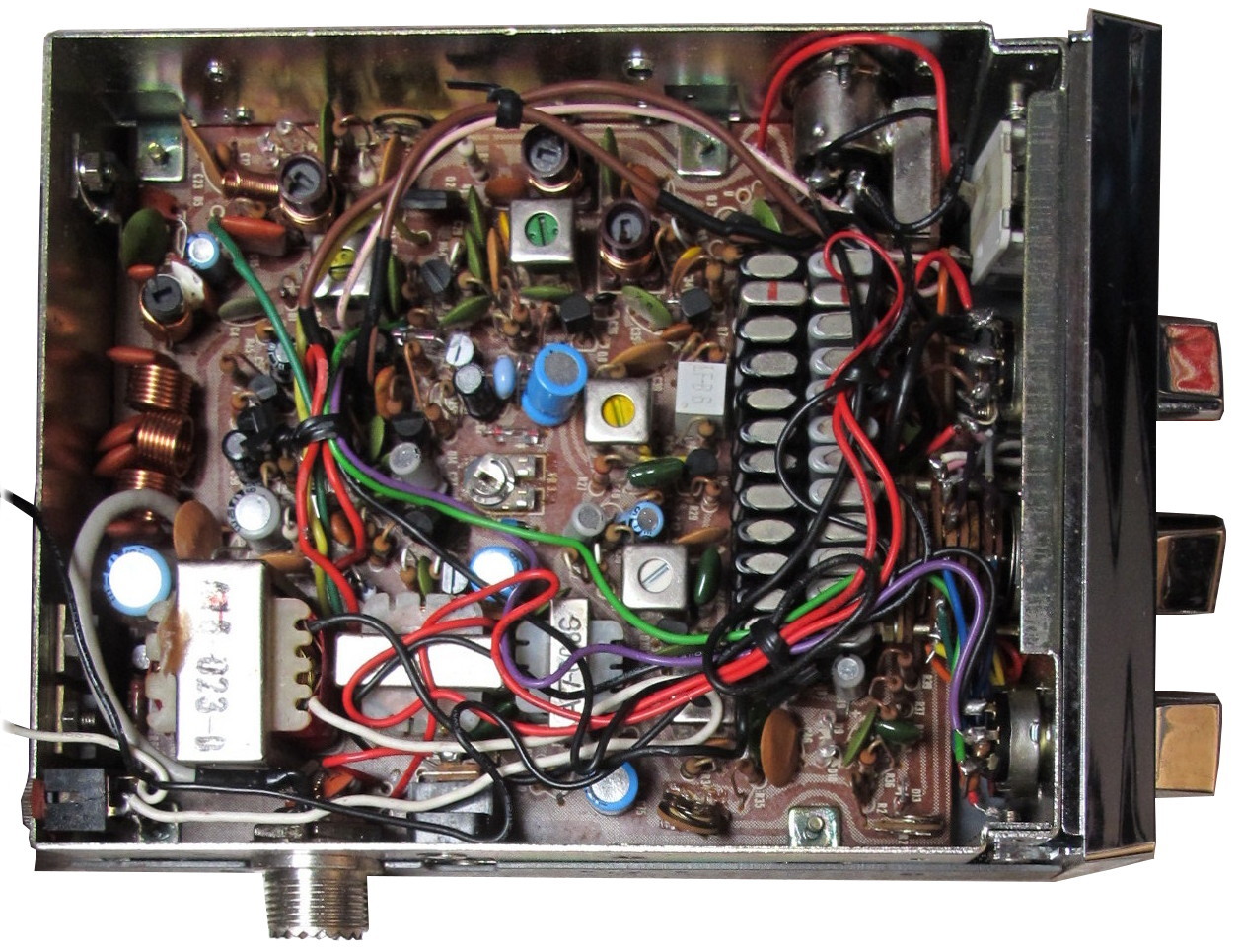

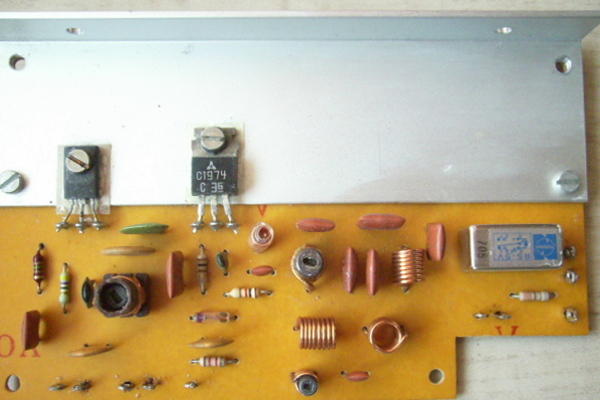

The photo shows the driver and output stages of such a transmitter. It is a self-assembled unit, made using etching techniques, used in a home-built radio. The relay visible on the far right is for switching the antenna from the receiver to the transmitter. The output stage, with its high-frequency grounded collector, operates with exceptional stability. In principle, this PA could also be connected downstream of the two-stage transmitter shown before.

Two-stage AM tube transmitter for 28...29.7 MHz

My first experiences with home-built two-way radio transmitters were in the upper shortwave range. Initially, I built circuits using transistors, which were widely published at the time in technical literature and electronics magazines for remote control purposes. After many failures, likely due to my lack of experience, I tried using vacuum tubes, following the instructions of Karl Schultheiß in "Der Kurzwellen-Amateur" (The Shortwave Amateur) and Werner W. Diefenbach in his "Amateurfunk-Handbuch" (Amateur Radio Handbook). I finally achieved my breakthrough with a circuit like shown here.

An output of approximately 4 watts could easily be achieved. Using the screen grid modulation shown, I achieved excellent results with minimal effort. A dedicated modulation transformer for anode-screen grid modulation was not available. With this screen grid modulation circuit, an ordinary output transformer from a salvaged tube radio could be used, and any transistor or tube amplifier with a 5-ohm output could be employed as modulation amplifier. The screen grid voltage of the EL84 tube had to be adjusted to approximately 140 volts using the 10kΩ trimmer (without modulation).

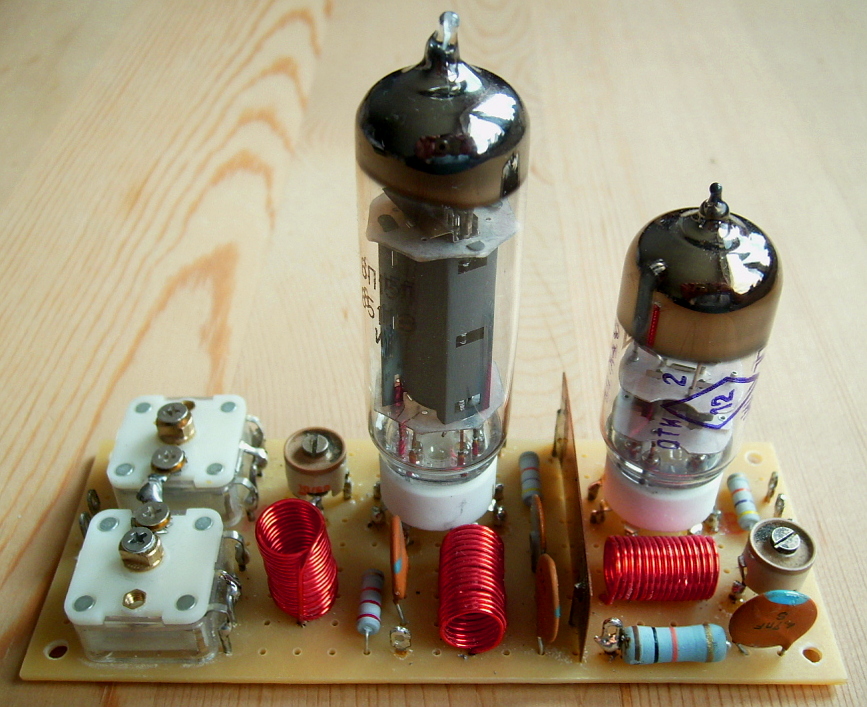

The photo shows a similar transmitter that I recently built for further experiments with this circuit design. It uses Russian a 6S3P tube in the oscillator and a 6P15P tube in the output stage and has comparable characteristics. However, the output power is somewhat lower. Additionally, the transmitter output includes a Pi filter tuned with two AM radio variable capacitors. It turned out that the Pierce oscillator, which is a parallel resonant oscillator, oscillates at a slightly too high frequency with most overtone crystals. The deviation for most such crystals is in the range of 2 to 6 kHz. This can be remedied by adding a tuning coil in series with the crystal, or even better, a trimmer capacitor in parallel with the crystal. Experimentation will quickly reveal the correct settings.

Fixed-frequency reflex superhet for the 10m band

This receiver is a complete superheterodyne receiver with an RF preamplifier, a mixer with a crystal-controlled oscillator, an AM demodulator, a two-stage IF amplifier with regulation, and a two-stage AF amplifier with a push-pull output stage. Due to the multiple use of stages, the circuit operates with a total of only six transistors. The RF preamplifier uses a 2SC1674 in common-base configuration. It has no special features and, together with the first IF stage, is regulated via the DC component of the AM diode modulator. The crystal-controlled oscillator also functions as a mixer. It is therefore a self-oscillating mixer stage, which, due to the crystal control, exhibits very good frequency stability. The second IF stage serves as a reflex stage and simultaneously as the AF preamplifier. It directly drives the subsequent push-pull output stage via the driver transformer.

Getting such a superheterodyne receiver to work was a particular challenge for me. Contrary to my fears, it wasn't that difficult at all. The key is a well-designed, RF-optimized construction with thoughtful routing. Considering the effort involved, the receiver had excellent input sensitivity and perfectly adequate overall gain. I experimentally inserted a ceramic filter after the first IF stage, which significantly improved the selectivity. Despite the considerably smaller effort, the overall performance then was almost on par with the receiver sections of older commercial manufactured CB radios (e.g., the DNT Meteor 5000).

10m fixed frequency superhet with TA7642 as IF unit

The receiver shown below can be built with minimal effort. It also operates on the superheterodyne principle. However, it uses the TA7642 IC, which is actually intended for use in simple, straight-through AM radios. This component is comparable to the ZN414 or the MK484. Here, it serves as an IF amplifier for 455 kHz and is characterized by good regulation properties for this purpose. Thus, the volume differences when receiving stronger and weaker stations are not excessively large. The DC voltage at the output pin, which decreases with increasing signal strength, can be used to operate an S-meter in a bridge circuit. It could also be used to drive a squelch circuit.

Since the IC is designed for operation on a 1.5V battery cell, the operating voltage is stabilized to a value of this order of magnitude using two silicon diodes connected in series in forward bias. The mixer and oscillator stage, equipped with a dual-gate MOSFET, operates as a self-oscillating, crystal-controlled mixer. This configuration produces very little inherent noise, thus ensuring good input sensitivity. Due to the crystal control, the receiver exhibits excellent frequency stability. Thanks to the ceramic filter, outstanding adjacent channel selectivity is achieved. Despite the minimal complexity, the characteristics achievable with this circuit, particularly regarding selectivity, are significantly better than those of the receiver sections of handheld transceivers from the early days of CB radio in Germany (e.g., Stabo Multifon Super 7 or DNT HF12).

I originally designed the receiver for remote control purposes (27 MHz), but also considered its potential use in portable 10-meter radios. Therefore, it would also be well-suited as a replacement for the superregenerative receivers in the handheld radios described elsewhere. With appropriate dimensioning of the resonant circuits (e.g., a 10.7 MHz IF filter with a parallel capacitor), the circuit could also be used for shortwave broadcast reception. For example, a 5615 kHz crystal would provide a simple and reliable receiver for DARC radio in the 49-meter band (6070 kHz AM). Since, in this case, there is no need to force the crystal to oscillate on the third harmonic, the MOSFET's oscillator circuitry could be designed aperiodically. The coil at gate 1 could then be replaced by a resistor connected in parallel with a fundamental-frequency crystal. This circuit configuration can be found in the 20m-40m converter, which I describe in another post.

Frontend for 28...29.7 MHz with tracking selection

The input circuit shown was part of a home-built transceiver for the 10-meter amateur band. It delivered very usable, and even better, results in terms of sensitivity, large-signal handling, and image frequency rejection compared to some commercially available devices. With the specified intermediate frequency (IF) of 10.695 MHz, almost complete image frequency rejection was achieved. An intermediate frequency amplifier for 455 kHz can be connected if a appropriate converter is added. A suitable circuit for this purpose is described elsewhere. Alternatively, the 10.695 MHz resonant-circuit at the output can be replaced with one for 455 kHz. In this case, however, significantly lower image frequency rejection is achieved, but this is usually sufficient thanks to the two-stage filtering between the preamplifier and mixer.

As can be seen in the circuit diagram, the intermediate circuits are designed as a tracking selector. The required control voltage is generated by a potentiometer mechanically coupled to the tuning VFO's variable capacitor. The risk of additional intermodulation from the tuning circuit was reduced by connecting each two varactor diodes in opposite directions. The RF preamplifier operates in a combined common-emitter and common-base configuration. In this arrangement, power and noise matching are achieved at the same point. Thus, by adjusting the input circuit for maximum signal, the best signal-to-noise ratio will achieved simultaneously. The mixer stage with the dual-gate MOSFET produced hardly any additional noise. Such circuits also exhibit significantly better large-signal handling characteristics than mixer circuits with a bipolar transistor.

IF amplifier for 455kHz with FET input

This IF amplifier uses a field-effect transistor (FET) at the input; otherwise, bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) are employed. Due to the high input impedance of the FET, the input-side IF circuit is hardly damped. The coupling winding can be connected to the coupling winding of the preceding mixer stage via a capacitor (e.g., 150 pF). In this way, this circuit can be connected, for example, directly after the 10.7 MHz / 455 kHz IF mixer described elsewere. In this way an IF unit for use in a dual-conversion superheterodyne arises. The coupling, and thus the bandwidth, can be influenced by the capacitor value. The output bandpass filter also consists of two separate resonant circuits, but these are operated with capacitive high-point coupling. Overall, this results in similar selectivity characteristics to a tube superheterodyne receiver with a single-stage IF amplifier. If these are insufficient, a ceramic filter can be inserted at the input.

An FM or SSB demodulator, for example, can be connected to the output labeled "ZF". The diode, which is actually used to generate the control voltage, can also be used for AM demodulation. The signal demodulated by it is available at the terminal labeled "NF". The voltage for an S-meter can also be taken from its cathode. Control is achieved via the left transistor, BC237B. As the signal voltage increases, its conductivity between emitter and collector rises. The resulting current flow causes an increasing voltage drop across the drain resistor, thus reducing the drain voltage of the FET and consequently its gain. Simultaneously, increasingly shorts the output signal from the FET stage at the collector to ground, resulting in a dual control effect. This allows for a control range that would otherwise require multiple stages, controlled by simple bias shifts. In this circuit, however, the control provided by a single IF stage is entirely sufficient for a complete superheterodyne receiver. The second IF stage, formed by the right-hand BC237B and a BC307B, provides high voltage gain and a sufficiently low-impedance output to feed the signal to the first output-side IF circuit via its coupling winding. Despite its relatively simple design, the circuit exhibits excellent overall characteristics. Selectivity and regulation are significantly better than in the typical two-stage configuration found in many transistor receivers and CB radios. In that devices, two transistor stages in common-emitter configuration were commonly used, coupled at the input, to each other, and between the output and demodulator via one of the individual IF circuits (yellow, white, black) also used here.