DIY receiver for beginners in amateur radio

Those interested in amateur radio used to begin by listening to radio communications on the amateur bands. However, for various reasons, this wasn't so easy. The shortwave range of most radio receivers started at around 5 MHz. This meant that the 80-meter band, very popular with many amateurs at the time, couldn't be received at all. Furthermore, a large part of radio communication took place using telegraphy, and in voice communication, single-sideband telephony replaced amplitude modulation during the 1960s. Neither telegraphy nor single-sideband signals can be received with a normal radio. Therefore, a special receiver was needed for amateur radio reception. Beginners in amateur radio, so-called newcomers, therefore gladly built self their receivers in the past.

Further articles on receiving amateur radio transmissions:

- regenerative receivers from various manufacturers

- Receiver kits for beginners developed by radio amateurs

- Superheterodyne receiver assembly RKT-100S from Radio-RIM

- Multi-range tube superhet Unica UR-400 for medium and shortwave

Simple shortwave receivers - possible with only one tube!

Specialized communication receivers, capable of precisely tuning amateur radio frequencies and receiving telegraphy and single-sideband signals, were very expensive. Such devices were not to be considered for those simply wanting to find out if amateur radio was the right hobby for them. Furthermore, amateur radio primarily attracted interest from younger people with naturally smaller financial resources. However, building a simple receiver capable of receiving telegraphy and single-sideband stations and suitable for various shortwave amateur bands was neither complicated nor expensive. This was achieved using the audion principle, where demodulation is accomplished through the non-linear characteristic curve of an amplifier tube operating without negative grid bias. Adjustable feedback of the high-frequency energy minimizes resonant circuit losses and significantly improves selectivity. Set slightly above the point of maximum regeneration, the circuit begins to oscillate at the selected frequency. In this state, the circuit functions as a self-oscillating product detector and therefore simultaneously as an oscillator, thus enabling the reception of telegraphy and single-sideband signals! Modifying a broadcast receiver to accommodate amateur radio transmissions required considerably more effort. It's no wonder, then, that such circuits were published and replicated in abundance, and that numerous kits were available.

Due to the simple principle, it wasn't strictly necessary to build such receivers exactly according to instructions. With tube circuits, component values usually don't need to be precisely adhered to. For example, the functionality often doesn't depend on whether a certain resistance has a value of 50, 100, or even 250 kilohms. The same applies to coupling and bypass capacitors. Therefore, such receiver designs could be easily adapted to existing components. These could be easily salvaged from discarded radios. Only the resonant circuit or tuning elements required precision, mechanical stability, and proper assembly. This made such projects an instructive pursuit that, with sufficient effort, was rewarded with correspondingly good reception characteristics. The choice of tubes was also not critical. For the audion, so the radio frequency section of the receiver, almost any preamplifier tube suitable for high frequencies was appropriate. Because of the gain concomitant with feedback, triode circuits were hardly less sensitive to reception than pentode circuits. However, their construction was simpler, and there were fewer problems with unwanted oscillations, which, with increased feedback, also could manifest as so-called superregenerative oscillations. With dual triodes such as the ECC81 or ECC85, the second triode section provides a dedicated tube for the audio amplifier. Without audio amplification, the receiver is only capable of making very loud radio stations audible through headphones. With just one additional audio amplifier stage, however, the amplification is sufficient for receiving weak stations, and with strong stations, even for a—albeit rather modest—loudspeaker reception. This results in a receiver that, externally, appears to operate with only a single tube!

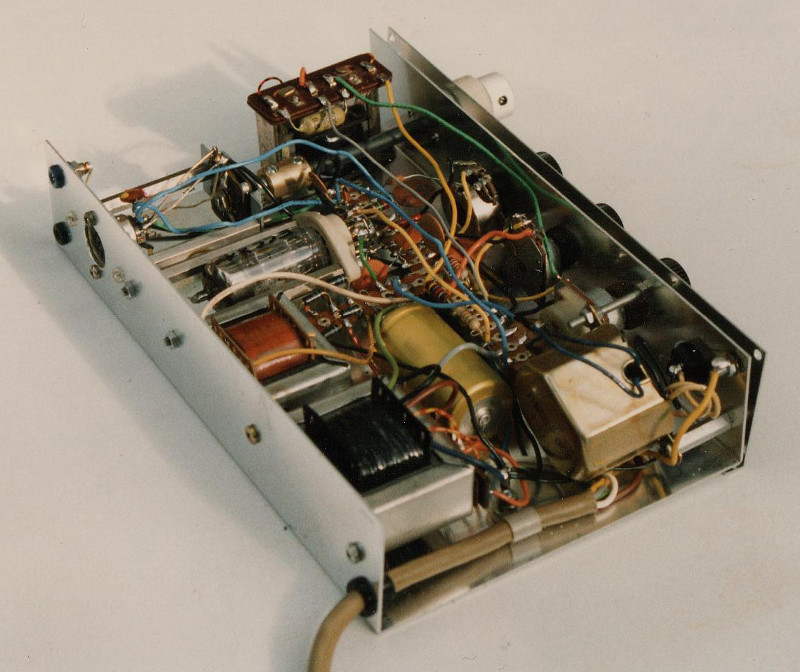

In the circuit shown above, the feedback was regulated with a second variable capacitor. This had the disadvantage that the receiving frequency changed when the feedback was justated. However, with some practice, this characteristic could be used to one's advantage by using the feedback control in its oscillating state for fine-tuning telegraphy and single-sideband stations. With different, interchangeable coil sets, a device built in this way allowed me to receive radio stations, amateur radio stations, coastal radio stations, and many other radio services from all over the world. It quickly became almost magical what could be heard! For example, if a radio or amateur station wished one good night on a currently tuned frequency, it could happen that after a minimal adjustment of the tuning on a different frequency, one would receive morning greetings from a completely different location on the globe. The circuit worked perfectly up to about 10 MHz; beyond that, tuning telegrahy and single-sideband stations, in particular, became somewhat difficult. By using a filter circuit in the antenna line to attenuate the local radio station, it was also possible to receive good medium-wave radio stations from all over Europe in the evening hours.

Single-tube radio receiver with reflex amplifier circuit

Based on the experience gained with this circuit, I later developed a receiver that incorporates several refinements with minimal effort. This device, too, was equipped with only a single ECC81 double triode. Here, the triode system of the ECC81, visible on the right side of the circuit diagram, operates in a so-called reflex circuit as an audio amplifier and simultaneously as an aperiodic, therefore not tuned to the receiving frequency, high-frequency preamplifier. While this results only in little gain in sensitivity, it effectively decouples the resonant circuit from the antenna. This noticeably improves frequency stability and also provides a small gain in amplification, allowing weak stations to be received somewhat louder. The triode audion built with the tube system on the left side of the circuit diagram performs better and more reliably in this configuration in many respects. Moving closer to the antenna or its feed line hardly causes any significant frequency changes. Other fluctuations in antenna capacitance, whose causes are often difficult to determine, have hardly any influence on the operating frequency of the audion. Furthermore, oscillation gaps—frequencies at which, especially with long or rigidly coupled antennas without a preamplifier, the feedback cannot be increased to the point of oscillation—are virtually eliminated.

Because the feedback adjustment is made with a potentiometer, the reception frequency changes only slightly when adjusted. This method is also characterized by a smooth feedback response. In addition to the input gain for the radio frequency, an optimized matching of the audion on the low-frequency input side of the reflex circuit results in a further increase in volume. This is achieved by a so-called auto-transformer between the audion and the reflex stage. Besides further increasing sensitivity, this also means that even weaker stations can be clearly heard not only with headphones but also with a connected loudspeaker.

In the shortwave spectrum, which was considerably more congested than today, this circuit could receive hundreds of broadcast stations and amateur radio stations around the mid-1970s under good propagation conditions. Furthermore, maritime radio, aeronautical radio, military stations, intelligence services, and numerous other radio services could be received with usable to good quality. Reception of CB radio stations was also successful, sometimes even from other countries. Such regenerative receivers demodulate the received signal directly at the set reception frequency. Hence a particularly advantage is the absence of image frequencies or other interference. Consequently, receivers of this type offer less interference in many situations compared to simple superheterodyne receivers (e.g., inexpensive world band receivers), even if the latter have better selectivity.

Even today, such a device is well-suited for receiving analog radio stations and amateur radio broadcasts. For shortwave broadcasting reception, and of course also for listening other amplitude-modulated transmissions, the feedback should be adjusted so that the regenerative detector is just on the verge of oscillating, wich achieves the maximum selectivity. If the feedback potentiometer is turned beyond this point, telegraphy signals and single-sideband modulated transmissions (SSB) can be received clearly. This setting is therefore chosen for receiving amateur radio transmissions. For sufficiently precise tuning, the tuning capacitor must be free of backlash and easy to operate. Many old broadcast tuning capacitors have a gear reduction (usually 1:3), which is generally insufficient for accurately tuning telegraphy or single-sideband transmissions. It is therefore recommended to use a fine-tuning mechanism with a larger reduction ratio, possibly even in addition to the gearing already present on the tuning capacitor. Furthermore, it is possible to connect a smaller-capacitance tuning capacitor (e.g., 12 pF) in parallel with the actual tuning capacitor for fine-tuning.

One disadvantage of the direct superposition principle for receiving single-sideband and telegraphy signals should not be concealed: There is no suppression of the unwanted sideband. Therefore, relative to the (suppressed) carrier frequency, the receiver always picks up both the upper and lower sidebands (USB and LSB) simultaneously. Stations transmitting on the same sideband, but slightly off-frequency, and thus falling into the range of the other sideband, cause unintelligible interference. However, this is usually only problematic during periods of heavy band congestion, such as during a contest or when activity is very high due to good propagation conditions. Incidentally, narrowband frequency modulation (NFM) transmissions can also be received excellently with such a circuit. These are usually only found on the higher shortwave frequencies, for example, in CB radio. To receive them, the tuning must be adjusted slightly above or below the actual receiving frequency. The feedback is adjusted as when receiving amplitude-modulated transmissions. This so-called flank demodulation usually works better with the regeneration receiver than with a superheterodyne receiver.

Despite its extremely simple circuitry, building such a receiver is not entirely straightforward. The reflex circuit must be constructed very carefully, for example, by ensuring that the wires between the individual circuit elements are as short as possible. This is particularly important for the high-frequency components, such as the tuning capacitor and the resonant circuit coil, as well as for capacitors connected to ground. The ground points of the reflex and audion stages should each be connected to their respective components in a star configuration. To gain sufficient experience for the optimal construction, you should first build the audion circuit presented earlier without the reflex stage!

Another difficulty is obtaining a suitable audio transformer. It's unlikely you'll find one ready-made these days. However, it can be made by rewinding a small output transformer from an old tube device. About one-fifth of the turns are unwound from the primary winding of such a transformer to create a tap. These turns are then rewound. A suitable replacement could also be created by combining two different transformers, resulting in two high-impedance windings with appropriate transformation ratios.

Further articles on receiving amateur radio transmissions:

- Xtal controlled fixed-frequency tube receivers for two-way radio reception

- Transistorized five band shortwave amateur radio superhet Semiconda 68 from Semcoset

- Small but powerful mini whip antenna for shortwave reception

Transistor regenerative receiver: best results by using FETs!

Numerous experiments have confirmed that transistorized regenerative receiver circuits cannot readily achieve comparable results to those of tube circuits. One problem is the relatively low input impedance, which strongly dampens the resonant circuit. The regeneration of the resonant circuit through feedback is therefore less effective than in a tube-based receiver circuit, resulting in lower selectivity. Further problems arise from the transistor capacitances, which change with the operating voltage and ambient temperature, significantly degrading frequency stability. Therefore, other circuit types must be used to receive telegraphy stations and single-sideband signals with satisfactory quality when feedback is applied to self-oscillation. Reception of such signals is further complicated by the fact that transistor circuits are prone to synchronization effects. The circuit's natural oscillation then essentially locks onto the received signal, preventing superposition at the signal peaks of single-sideband signals. This manifests as very strong signal distortion.

While a Darlington configuration consisting of two transistors allows for a higher input impedance, it exhibits less favorable characteristics at high frequencies. Therefore, using a single transistor with a high current gain is preferable. Feedback from the emitter to the base with capacitive voltage division, similar to a Colpitts oscillator, improves frequency stability because larger capacitances are connected in parallel with the internal transistor capacitances. The influence of the internal transistor capacitances on the frequency is then significantly reduced. Furthermore, using a field-effect transistor (FET) instead of a bipolar transistor in the audion is far more advantageous. This results in a considerably higher input impedance and correspondingly lower damping of the resonant circuit. Additionally, the different characteristics of FETs reduce synchronization effects. It has been shown that, in suitable circuit configurations, these transistors can achieve results very close to those of vacuum tube circuits.

The circuit diagram shows an audio receiver with a field-effect transistor (FET) that exhibits very usable characteristics despite its minimal circuitry. A device built according to this circuit, despite its extremely simple design, offered very usable reception of amateur radio transmissions in telegraphy and also with single-sideband modulation. It was also well-suited for receiving amplitude-modulated broadcast stations in the 75m, 60m, 49m, and 41m broadcast bands. Feedback is achieved here in the manner described, using capacitive voltage division. Since it is a field-effect transistor, the feedback path runs from the source to the gate. Compared to a similar circuit with a bipolar junction transistor (BJT), this arrangement offered significantly higher gain and output capability with improved selectivity. Furthermore, synchronization effects only occurred at very strong signal levels. The feedback adjustment was implemented using a potentiometer in the source line, which shifts the operating point of the field-effect transistor and thus influences the high-frequency gain. To achieve the highest possible voltage for the demodulated audio signal, the potentiometer is bypassed with an electrolytic capacitor. A single-circuit intermediate frequency filter from the FM section of a Japanese transistor radio was used as the resonant circuit, eliminating the need to wind a suitable coil. With the specified 500pF variable capacitor, a range encompassing both the 80m and 40m bands could be tuned when the coil core was turned in. However, sufficiently fine tuning—especially for single-sideband stations—required a good mechanical fine-tuning mechanism for the variable capacitor. Alternative options would be to connect a smaller variable capacitor in parallel, for example with a final capacitance of approximately 10 pF, for fine-tuning, or to use band spreading with series and parallel capacitors in the resonant circuit. These capacitors can then be selected so that only the desired frequency range can be tuned at any given time. Without changing the coil switching between these capacitors could then be implemented, allowing the device to selectively receive either the 80m or the 40m band.

The audio amplifier, featuring an LM386 integrated circuit, delivers some hundred milliwatts of power, enabling excellent loudspeaker reception even from weak stations. Its gain can be adjusted by connecting a resistor in series with the 10µF electrolytic capacitor. Bypassing the resistor results in a gain of approximately 200, but depending on the circuit design, this can lead to low-frequency oscillations, manifesting as unwanted noise such as humming or squealing. For use with a particularly efficient loudspeaker or for headphone reception, the series combination, or the 10µF capacitor, can be omitted entirely. In this case, the gain of the audio frequency section is only about 20, ensuring exceptionally stable operation. A series trim resistor allows to adjust the gain. A suitable value for this purpose would be 1 kΩ.

From the very simply constructed audion, a circuit for a remarkably effective regeneration receiver was developed, in which the field-effect transistor serves only as a demodulator. The Feedback to eliminate the losses in the resonant circuit is provided by an additional bipolar transistor. As with the previous circuit, the field-effect transistor for feedback operates in a drain-based configuration, while demodulation takes place in a source-based configuration. In an amplifier stage with the bipolar transistor, the radio-frequency signal undergoes voltage amplification from the drain terminal and is then fed back to the resonant circuit. This arrangement eliminates the need for taps or coupling coils at the resonant circuit coil. A further advantage is that the field-effect transistor can be operated with a fixed operating point, independent of the feedback setting. This point is selected to achieve low-distortion demodulation of the received stations. In this configuration, the field-effect transistor can simultaneously achieve good gain.

The reception characteristics achievable with this circuit are therefore even better compared to the previous circuit. Furthermore, to ensure good frequency stability, the supply voltage to the high-frequency section of this receiver is stabilized by a Zener diode. The large value of the capacitor between the source of the field-effect transistor and the emitter of the bipolar transistor was chosen to enable the circuit to oscillate even in the longwave range. Depending on the dimensions of the resonant circuit, the circuit is suitable for reception frequencies from approximately 160 kHz up to over 30 MHz. If longwave and mediumwave reception is not required, the value of this capacitor can be significantly reduced (e.g., 1 nF instead of 22 nF). The value of the capacitor from the collector to the resonant circuit can also be smaller (e.g., 33 pF instead of 100 pF). These two changes improve the circuit's performance in the shortwave range.

Because the resonant circuit coil requires no taps or coupling windings, it can be easily implemented as a plug-in coil. This allows for simple switching of the reception band. Speaker DIN connectors and sockets (dash-dot standard) have proven effective for this purpose, providing good contact and consequently low resonant circuit losses. In principle, the entire range from the lower end of longwave to the upper end of shortwave (30 MHz) can be covered with five coils. However, it is advisable to spread the bands using parallel capacitors and distribute them across a larger number of sub-bands. Of course band switching with a switch is also possible. Rotary switches with hard paper insulation are suitable, but ceramic versions are preferable. For precise tuning of stations operating in telegraphy or single-sideband modulation, fine-tuning should be provided. It is also well-suited for receiving stations using narrowband frequency modulation (e.g., CB radio), as precise tuning to the upper or lower edge of the signal is required. For fine-tuning, a small variable capacitor with a maximum capacitance of approximately 10 or 12 pF, connected in parallel to the main tuning capacitor, also is suitable here again. Alternatively, a varactor diode tuning circuit can be used. If the receiver is to be expanded with an FM unit, this can also be tuned using the same potentiometer. A good solution for the FM section would be realized by using an integrated circuit of type TDA7000. With a view to sound quality and achievable volume when receiving broadcast stations, the receiver was equipped with a audio amplifier using an integrated circuit of type TDA2003.