This is how a Wadley loop receiver works

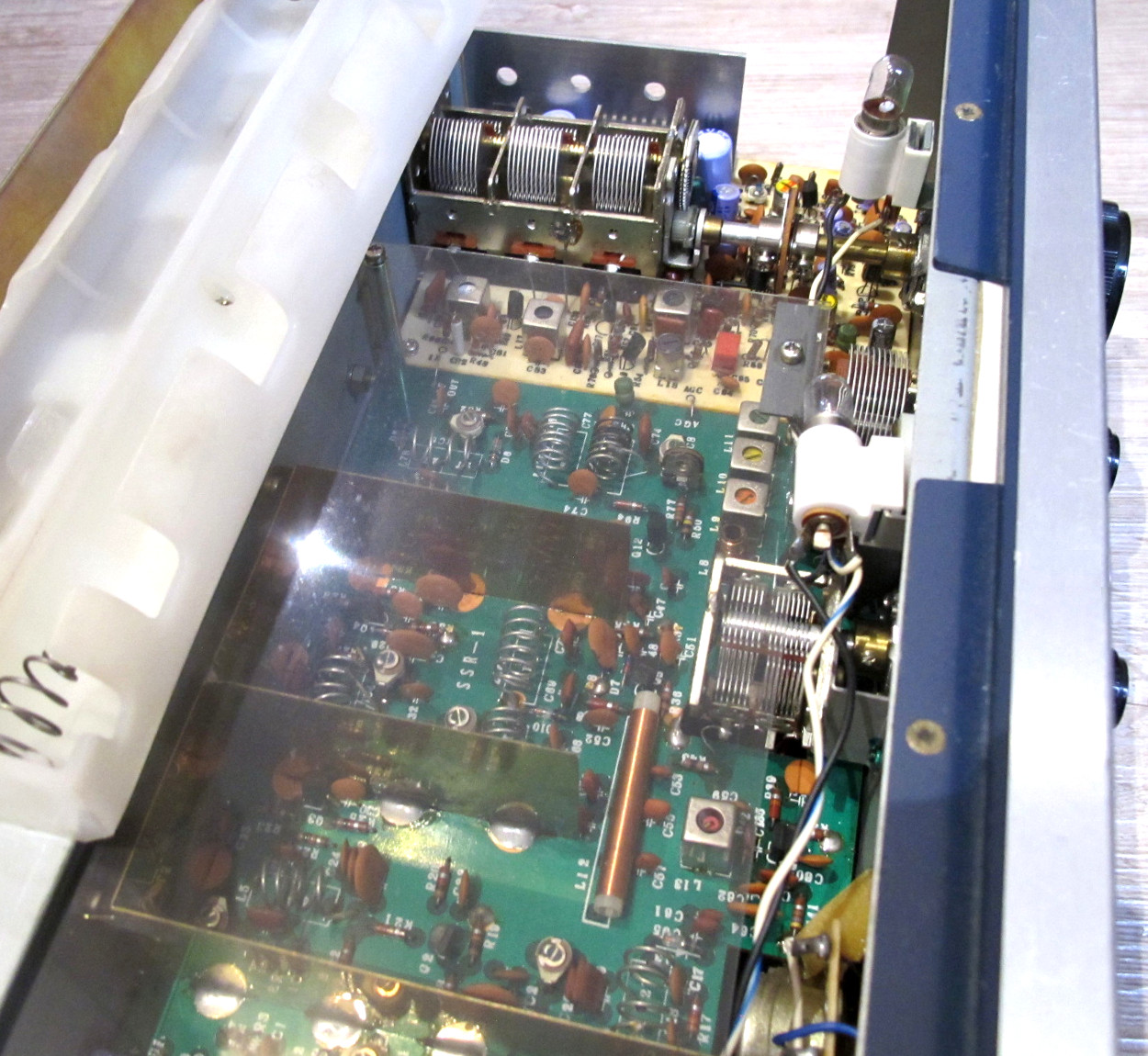

At this point, I will attempt to briefly and concisely explain the operation of a Wadley loop receiver. It is a principle that gained widespread use in commercial radio technology in the late 1950s. The receivers from Racal, which at that time still used vacuum tubes, operated on this principle. The Wadley loop is therefore an analog method. This allows shortwave receivers to be designed for a wide frequency range without the need for complex band switches. It was first found in the South African-made Barlow Wadley XCR-30, a receiver intended for shortwave listeners and amateurs. Other receivers operating on this principle included the Drake SSR-1, the Yaesu FRG-7, the Standard C-6500, and the Tandy DX-300. With the advent of digitally controlled oscillators, the principle lost its significance.

Developed in the 1940s by the South African Dr. Trevor Wadley, this principle is based on the superheterodyne principle. It was initially used for precise wavemeters. When used in a receiver, a triple superheterodyne receiver (at least) is required to process the received signal from the receiver input to the demodulator. Since an additional mixing stage is needed with the loop mixer, this results in a total of four mixing stages. Through a special processing of the superheterodyne frequencies, the reception range up to 30 MHz is divided into equally sized segments, each 1 MHz wide. This even works below 1 MHz. In a double superheterodyne receiver with a crystal-controlled first oscillator, 30 crystals with a frequency spacing of 1 MHz each would be required. The Wadley triple superheterodyne receiver requires only a single crystal!

In summary, the Wadley principle offers the following advantages:

- continuous reception range from below 1 to 30 MHz

- same scale calibration in all 1MHz segments

- good tunability in the segments only 1 MHz wide

- high and consistent frequency stability in all ranges

- the need for adjustment of intermediate and pre-circuits is eliminated

In all segments, the actual tuning takes place over a range of 1000 kHz. Accurate scales can easily be manufactured for this purpose. A more precise display is also possible in principle with a frequency counter for the tuning VFO, even with the Wadley receiver. Due to the limited 1000 kHz tuning range, the fine-tuning mechanism for the tuning knob does not require excessively high specifications. Consequently, high repeatability can be achieved despite minimal electrical and mechanical complexity.

The block diagram shows that signals from the antenna reach the RF preamplifier via a preselector. A single circuit tuned to the receive frequency is sufficient as a preselector. Due to the high first IF, image frequencies can be effectively eliminated with a low-pass filter between the preamplifier and the first mixer. The latter converts the signal, depending on the set frequency, into a range of 39.5 to 40.5 MHz within a 1 MHz segment. The reason why the 40 MHz IF filter is 300 kHz wider will be explained later. The first mixer receives its injection signal from the band-setting VFO. It operates above the first IF and can be tuned from 40.5 to 69.5 MHz. It selects the 1 MHz wide receive segments. The signal passes through the first IF filter to the second mixer. Simultaneously, the signal from the band-setting VFO is fed to the loop mixer. Here, it is mixed with the harmonic spectrum of a quartz-stabilized 1 MHz signal. This extends from 3 to 32 MHz. Harmonics above this range are suppressed by a low-pass filter.

The output signal of the loop mixer is further processed in a selective or bandpass amplifier. This amplifier only amplifies mixing products in the range of 37.5 MHz ± 150 kHz. The resulting signal serves as the injection signal for the second mixer. This mixer blends the first intermediate frequency (IF) into the second IF, which lies in the 2 to 3 MHz range. The subsequent circuitry operates like a conventional single-conversion superheterodyne receiver for the 2 to 3 MHz range. The variable frequency oscillator (VFO) used here is responsible for the actual receiver tuning. The high stability required here is crucial for the overall stability of the receiver. At the low frequencies with a tuning range of 2.455 to 3.455 MHz, this stability is easily achievable.

The stability requirements for the band-setting VFO are minimal because any frequency drift results in a corresponding frequency change in the first IF. With deviations of ±150 kHz, the correspondingly deviating first IF is always processed correctly due to the overall 1.3 MHz wide filter. The 37.5 MHz mixing product is also permitted to deviate from the target frequency due to the 300 kHz wide selective amplifier. However, this deviation has a counteracting effect on the received frequency via the second receive mixer, so that ultimately, a frequency drift of ±150 kHz is imperceptible during reception.

To illustrate this, consider a practical example where the receiver is tuned to a frequency of 14 MHz. Naturally, the preselector is set to this frequency. Let's assume the band-setting VFO is set to 54.5 MHz, resulting in a first intermediate frequency (IF) of 40.5 MHz. The loop mixer creates a difference of 37.5 MHz from 54.5 MHz and the 17th harmonic of the crystal oscillator. This amplified and filtered signal is then fed to the second receive mixer. Mixed with the first IF, this results in a second IF of 3 MHz. Therefore, the tuning VFO must be set to 3.455 MHz.

Now let's consider the situation when the 14 MHz signal is to be received in the adjacent segment. For this, the band-setting VFO would need to be tuned to 53.5 MHz, resulting in a first intermediate frequency (IF) of 39.5 MHz. The 37.5 MHz injection signal is then generated by mixing the 53.5 MHz signal with the 16th harmonic of the 1 MHz crystal oscillator. The first IF of 39.5 MHz and the 37.5 MHz injection signal combine to create a second IF of 2 MHz. Therefore, the tuning VFO must now operate at a frequency of 2.455 MHz.

These two examples demonstrate that all frequencies falling exactly on whole MHz can be received in two adjacent segments. The tuning VFO is tuned once to the upper end of the band and once to the lower end. Only the frequency of 30 MHz can be received only once, namely at the upper end of the band in the uppermost segment. The theoretically possible lowest frequency of 0 Hz is, of course, not achievable. The lowest receive frequency can, in principle, lie in the very low frequency range and is essentially determined by the design of the preselector.

The band-setting VFO only needs to be roughly tuned to the frequency appropriate for the desired reception range. Its scale therefore does not need to be highly accurate. For example, if it is tuned to 41.5 MHz, the reception range is 1 to 2 MHz; at 42.5 MHz, it is 2 to 3 MHz, and so on. It will now be shown that a slight mistuning or frequency drift of the band-setting VFO has no adverse effect on reception. Referring to the example of receiving a 14 MHz signal, let's assume the band-setting VFO has drifted to a frequency of 54.6 MHz instead of 54.5 MHz. In this case, the first intermediate frequency (IF) is now 40.6 MHz. Theoretically, a 1 MHz wide filter would be sufficient for the receiver in the IF stage. However, to compensate for such a frequency drift in the practical receiver design, the 40 MHz filter allows a range of ± 650 kHz to pass through. Otherwise, a first IF signal of 40.6 MHz would no longer reach the second mixer.

The same applies to the 37.5 MHz signal generated by the loop mixer. With a frequency of 54.6 MHz deviating from the bandset VFO, mixing with the 17th harmonic of the crystal oscillator results in a frequency of 37.6 MHz. Since the selective amplifier for 37.5 MHz has a bandwidth of ±150 kHz, this signal also passes unimpeded to the second mixer. Just as with an exact tuning of the bandset VFO to 54.5 MHz, a deviation to 54.6 MHz with a first IF of 40.6 MHz and an injection frequency of 37.6 MHz at the output of the second mixer also results in a second IF of 3 MHz. This demonstrates that deviations of the bandset VFO are automatically compensated in this way. For frequency deviations exceeding ±150 kHz, only the signal strength initially decreases at the filter slopes. This is the primary reason why such a setting should be avoided; however, it has no effect on the receiving frequency. In practice, designing a VFO for the 40.5 to 69.5 MHz range with a stability better than ±150 kHz is not a major problem.

For a Wadley receiver to function correctly and achieve good receiver characteristics, efficient low-pass and band-pass filters are required. Furthermore, careful construction and good shielding between the various stages are essential. Otherwise, for example, the harmonics of the 1 MHz crystal oscillator will be received. To reliably prevent this, the power supply lines must also be carefully decoupled with capacitors and, if necessary, filtered with RF chokes. A multi-chamber design is recommended. Considering the savings in circuitry and mechanical complexity that this design achieves, as well as the excellent reception and usability, the effort is well worth it. The result is a receiver that, with a little practice, can be tuned precisely and very quickly to any desired frequency within the reception range.

Source: Ian Pogson, Electronics Australia, January 1971

© Claus Schmidt, DL4CS